This is the third and last installment of the three naval battles which saved the WEST from Eastern or North African domination. The previous two naval engagements, I already posted: SALAMIS in 480 BCE and ACTIUM in 31 BCE.

Gaining supremacy of the Mediterranean basin was of supreme strategic importance for whoever ruled the sea could then invade southern Europe at will, anywhere from Greece to Spain. Occupying Sicily and southern Italy which are at the center of the Mediterranea would be the first tactical objective to be used as the jumping off point for a future invasion of Europe. In the VIII th century, the Arabs did conquer Sicily and Sardinia and kept them for 300 years. Now, 500 years later, was the time of the OTTOMAN Turks.

OTTOMAN EMPIRE

SHOWING LEPANTO

THE NAVAL BATTLE OF

LEPANTO - 1571

The Battle of Lepanto

was a naval

engagement taking place on 7 October 1571 in which a fleet of the

Holy

League, a coalition of European Catholic

maritime

states arranged by Pope

Pius V, financed by Habsburg

Spain and led by admiral John

of Austria, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of the Ottoman

Empire in the Gulf

of Patras, where the Ottoman forces sailing westwards from their

naval station in Lepanto

(the Venetian name of ancient Naupactus

Ναύπακτος,

Ottoman

İnebahtı)

met the fleet of the Holy League sailing east from Messina,

Sicily.

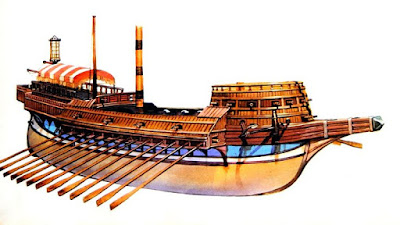

In the history

of naval

warfare, Lepanto marks the last major engagement in the Western

world to be fought entirely or almost entirely between rowing

vessels, the galleys

and galeasses

which were still the direct descendants of the ancient trireme

warships. The battle was in essence an "infantry battle on

floating platforms". It was the largest

naval battle in Western history since classical antiquity,

involving more than 400 warships.PREAMBULE

The Christian coalition had been promoted by Pope Pius V to rescue the Venetian colony of Famagusta, on the island of Cyprus, which was being besieged by the Turks in early 1571 subsequent to the fall of Nicosia and other Venetian possessions in Cyprus in the course of 1570. On 1 August, the Venetians had surrendered after being reassured that they could leave Cyprus freely. However, the Ottoman commander, Lala Kara Mustafa Pasha, who had lost some 50,000 men in the siege, broke his word, imprisoning the Venetians. On 17 August, Marco Antonio Bragadin was flayed alive and his corpse hung on Mustafa's galley together with the heads of the Venetian commanders, Astorre Baglioni, Alvise Martinengo and Gianantonio Querini.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Battle of Lepanto took place between the Holy League, consisting of Spain, Venice and the Papacy, and the Ottoman Empire, which lay to the south of Poland and Russia. Two thirds of the Holy League ships were Italian, but Spain contributed most of the financing. The Holy League, under the command of Don Juan of Austria, met the Ottoman fleet, led by Ali Pasha, at Lepanto on 7th October 1571.

THE HOLY LEAGUE

The members of the Holy League were the Republic of Venice, the Spanish Empire (including the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdoms of Sicily and Sardinia as part of the Spanish possessions), the Papal States, the Republic of Genoa, the Duchies of Savoy, Urbino and Tuscany, the Knights Hospitaller and others.

THE LEAGUE'S COMMANDERS

John of Austria (24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578), in English traditionally known as Don John of Austria, in Spanish as Don Juan de Austria[1] and in German as Ritter Johann von Österreich, was an illegitimate son of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. He became a military leader in the service of his half-brother, King Philip II of Spain and is best known for his role as the admiral of the Holy Alliance fleet at the Battle of Lepanto

Marcantonio II Colonna (sometimes spelled Marc'Antonio; 1535[1] – August 1, 1584), Duke of Tagliacozzo and Duke and Prince of Paliano, was an Italian aristocrat who served as a Viceroy of Sicily in the service of the Spanish Crown, Spanish general, and Captain General of the Church. He is best remembered for his part as the admiral of the Papal fleet in the Battle of Lepanto.

Sebastiano Venier (or

Veniero) (c. 1496 –

3 March 1578) was Doge

of Venice from 11 June 1577 to 3 March 1578. He is best

remembered in his role as the Venetian

admiral at the Battle

of Lepanto.

The Victors of Lepanto (from left: John of Austria, Marcantonio Colonna, Sebastiano Venier)

Sultan Selim II

Selim II was the third in a row son of Suleyman the Magnificent and the sultan's beloved wife Haseki Hürrem, of Ukranian origin. Selim was proclaimed 11th sultan of the Ottoman Empire and 90th Chaliph of Islam on September 7th 1566 and then went off to Belgrade to meet his army.

ALI PASHA

True Likeness

of the beheaded Turkish officer Ali Bassa [Ali Pasha], anonymous

German broadsheet, c.1571, woodcut with stencil and hand colouring

on laid paper with letterpress. Museum no. E.912-2003

This fascinating and rare print was published in Germany probably shortly after the allied Christian naval victory over the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Ali Pasha, the defeated Turkish naval commander is shown full length, wearing a kaftan of costly woven, figured silks. His exotic clothes, turban and long feathery headdress denote his high rank. Although he is shown alive, in the background is a detail of his head on the end of a pole. Behind Ali Pasha is the Turkish flagship on which he was wounded and subsequently beheaded. He was beheaded by a Spanish soldier, who brought his trophy to his commander. Some sources say that Don Juan then had Ali Pasha's head mounted on a pike, and others say that Don Juan was so infuriated with the lack of respect shown to his adversary that he ordered both the head and the man who had cut it off to be thrown overboard.

Uluç/Uluj Ali

Portrait of Uluç Ali Uluç Ali, known also as Uluç Ali Reis and later as Kiliç Ali Pasha in the Ottoman sources and as Occhiali in the western forces, was a legendary figure of Ottoman history. He was born in 1519 at Calabria, Southern Italy, as Giovanni Dionigi Galeni, he was the son of a mariner.

Occhiali (also Uluj Ali, Turkish: Uluç Ali Reis, later Uluç Ali Paşa and finally Kılıç Ali Paşa; 1519 – 21 June 1587) was a corsair (privateer) who later became an Ottoman admiral (Reis), Bey of the Regency of Algiers, and finally Grand Admiral (Kapudan Pasha) of the Ottoman fleet in the 16th century.

Born Giovanni Dionigi Galeni, he was also known by several other names in the Christian countries of the Mediterranean and in the literature also appears under various names. Miguel de Cervantes called him Uchali in chapter XXXIX of his Don Quixote de la Mancha. Elsewhere he was simply called Ali Pasha.

Mehmed Suluk Pasha.

Also known with the nickname “Sirocco”, i.e.

southern wind, Mehmed Suluk was Bey of Alexandria at the time of the

naval battle of Lepanto. He had rolled up in the Ottoman fleet at

the age of 18 and had had a glorious career, particularly as an

infantry fighter. At Lepanto he

was appointed commander of the right flank of the Ottoman fleet, but

he didn't manage to win the Venetians who fought against him and he

was seriously injured. He managed to escape, but the Venetians

persecuted him and finally arrested him. He was then asked to be

spared the suffering and the Venetian officer killed him on the spot. Mehmed Siroco headed the Turkish right wing (at top

right) during the 1571 Battle

of Lepanto, where both him and the commander of the opposing Holy

League left wing, Agostino

Barbarigo, were killed in action.

Belligerents

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

Ottoman Empire |

Commanders and leaders

|

|

|

Left:

Right:

Reserve:

|

Ottoman

Navy:Center: Sufi Ali Pasha †Right: Mahomet Sirocco †Left: Uluç Ali (Occhiali) |

Strength

|

|

212 ships[3]

1,815 guns[7]

|

251 ships

31,490

soldiers

750 guns50,000 sailors and oarsmen |

Casualties and losses

|

|

7,500 dead

17 ships lost[8] |

20,000 dead, wounded or captured 137 ships captured 50 ships sunk 12,000 Christians freed |

NOTE

The Battle of Lepanto took place between the Holy League, consisting of Spain, Venice and the Papacy, and the Ottoman Empire, which lay to the south of Poland and Russia. Two thirds of the Holy League ships were Italian, but Spain contributed most of the financing. The Holy League, under the command of Don Juan of Austria, met the Ottoman fleet, led by Ali Pasha, at Lepanto on 7th October 1571.

BATTLE PLAN

A. The rallying of the forces of the Holy League

As general commander of the allied forced had been appointed, following Philip's demand, his half-brother Don Juan of Austria, aboard the flagship La Real. The ships of the Holy League set off from Barcelona, Genoa, Rome, Venice, Malta, Corfu and Crete in order to gather at the Sicilian port of Messina. On September 17th 1571 the allied fleet comprised over 270 ships (206 galleys, 6 galeasses and 70 firkatas together with auxiliary ships). Aboard these ships were at least 28.000 men, of which 8.000 are estimated to have been Greeks, serving as mercenaries. The entire manpower, together with the rowers and the auxiliary personnel is estimated by some historians to have been about 70.000 men.

B. The rallying of the forces of the Ottoman Empire

Upon receiving the news of the rallying of the Holy League's fleet, the Ottoman Sultan Selim II proceeded to the rallying of an even larger fleet. The naval force of the Ottomans consisted of the fleet which was active at the Cyprus campaign, as well as of allied forces from Cairo and Algiers. The total number of ships reached 328, of which 208 were Ottoman galleys, 56 galliots and 64 fustas. Muezzinzade Ali Pasha was appointed commander general and he came aboard his flagship, the Sultana. The largest part of the fleet was initially rallied around Corfu and the neighbouring Albanian shores, where it stayed for most part of August. As the summer came to its end, though, and the threat of war seemed to fade away, the Ottoman fleet headed towards Naupaktos (Inebahti at the time).

Why was the holy league victorious

Because of the superior fire power of the GALLEAS

Notice the multiple canons emplacement which could fire sideways, not only in front. They covered a 180 degree field of fire.

John of Austria had a total of 6 Galleas

in the center ... and 4 others in reserve.

THIS PHOTO SHOWS THE GALLEAS CANONS WHICH BROKE THE FORMATION OF THE OTTOMAN GALLEYS

The Holy League was victorious in the Battle of Lepanto, losing twelve galleys to the Ottoman's one hundred and seventeen. The Ottomans had underestimated the fighting power of their opponent's fleet. They had heard of tensions within the Holy League and assumed that the Venetians would defect, and a reconnaissance mission carried out two days before the battle reported that there were significantly fewer Holy League ships than there actually were.

Although the Ottomans still had more ships in their command, they were outnumbered in fighting men and artillery.

Ali Pasha, commanding the forces against the Holy League, is otherwise known as Müezzinzâde Ali Pasha. He was married to one of the Sultan's daughters, and was appointed to the post of kapudan by Grand Vizier Mehmet Sokoli.

picture

RECORDS MYTH & LEGEND

The uncertainty of events and the heroic light

thrown on various members of both sides show how myth has surrounded

the battle. One historian of the battle relates how it 'was invested

with a miraculous aura at the time'. It was the last time the papacy

was able to direct violence against a rival of Christianity before

the wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants divided

Europe. No galley battle on such a large scale had been fought before

the Battle of Lepanto since ancient times, and it was never repeated.

It is perhaps this sense of it being the last battle that had made it

into such a celebrated victory. Indeed at the time, it was hailed as

the end of the Muslim threat to Christianity, which was felt

particularly deeply, it has been claimed, because of the contemporary

perception in the Christian lands that all of humanity was in crisis.

To defeat the Ottomans at Lepanto, they felt, was to rid themselves

of one of the greatest threats to western safety.

The uncertainty of events and the heroic light

thrown on various members of both sides show how myth has surrounded

the battle. One historian of the battle relates how it 'was invested

with a miraculous aura at the time'. It was the last time the papacy

was able to direct violence against a rival of Christianity before

the wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants divided

Europe. No galley battle on such a large scale had been fought before

the Battle of Lepanto since ancient times, and it was never repeated.

It is perhaps this sense of it being the last battle that had made it

into such a celebrated victory. Indeed at the time, it was hailed as

the end of the Muslim threat to Christianity, which was felt

particularly deeply, it has been claimed, because of the contemporary

perception in the Christian lands that all of humanity was in crisis.

To defeat the Ottomans at Lepanto, they felt, was to rid themselves

of one of the greatest threats to western safety.BATTLE WAS IN FACT INDECISIVE

Ultimately, however, the battle was indecisive. There was no permanent adjustment to power in the Mediterranean. The "crusading pope", Pius V, died in 1572, and Venice withdrew from the Holy League alliance the following year, having not reached their aim of recapturing Cyprus. The Ottomans made a quick recovery, and captured Tunis in 1574. Philip II, King of Spain, was nearly bankrupt and unable to prevent them. Further Spanish and Portuguese attempts to expand their North African territories were repulsed. Nevertheless, the Ottomans were also fighting in Persia and did not have the resources to continue their Mediterranean advance. In 1578 an informal suspension of arms was agreed with Spain, and in 1580 this became a permanent truce.

LEGACY

Despite this, the Battle of Lepanto was very much depicted at the time as a victory of Christian forces over Muslim: as good over evil, although today we know that the Muslims in the sixteenth century were no more or less cruel than the western Europeans, and were far more civilised. In addition, they were a lot more tolerant of Judaism and Christianity than the Christians were of Islam and Judaism.

Nevertheless, both sides saw the conflict as a religious battle. Letters between the Ottoman generals refer to the Christian forces as "the Infidels", while letters within the Holy League call the battle the cause of God. For the Holy League, the military monastic orders, such as the Order of Saint John and the Order of Santo Stefano, played a significant role. The anniversary of the Battle of Lepanto is still celebrated by the Catholic Church in the feast of Our Lady of the Rosary.

The legacy of the Battle of Lepanto has been strong as it was one of the first major events to occur after printing technology had become widespread, and it was a rare opportunity for late Renaissance artists to depict a contemporary victory. Therefore it saw wide coverage at the time from both printed and artistic sources. The Ottomans were celebrated as being heroic, worthy opponents, and the victory was commemorated throughout Western Europe as being a great triumph for Christianity, as the deliverance of Christendom from an oppressor, even it seems, in areas where Protestantism was favoured over Catholicism, such as in Germany. Perhaps the celebration there was, as one historian has cynically put it, more to do with the fact that the battle diverted papal attention away from the increasingly powerful Protestant strand of Christianity, which, with Catholic attentions elsewhere, was able to consolidate its INFLUENCE.

No comments:

Post a Comment